In modern manufacturing, pure metals are rarely the stars of the show. While elements like iron, copper, and aluminum possess remarkable individual qualities, they are often too soft or reactive to meet the demands of industrial applications. To solve this, we rely on alloys—metallic substances engineered by combining two or more elements to create a material that is superior to its constituents.

I. What Is an Alloy?

At its core, an alloy is a material composed of a primary metallic base (the solvent) and additional metallic or non-metallic components (the solutes) added as property modifiers.

Unlike a simple mixture, an alloy is a solid solution or a complex chemical compound where the added elements are integrated into the crystal lattice of the base metal. This “tuning” allows engineers to create materials that are stronger, harder, and more durable than pure metals.

II. The History of Alloys: From Accidental Smelting to Formal Science

The history of human civilization is often categorized by the alloys we mastered:

The Bronze Age (3000 BCE): Early metallurgists discovered that smelting copper and tin together created a metal hard enough to hold an edge—transforming warfare and agriculture.

The Iron Age (1600 BCE): The transition from bronze to wrought iron was a massive leap. Early “steel” was often made by accident as carbon from charcoal fires integrated into the iron during smelting.

The Industrial Revolution (18th-19th Century): This period saw the birth of formal metallurgy. Scientists isolated elements like Nickel, Chromium, and Manganese, leading to the high-performance stainless steels and superalloys we use today.

III. Atomic Structure: How Alloys Achieve Their Strength

To understand why alloys outperform pure metals, we must look at their microstructures. In a pure metal, atoms are arranged in orderly, uniform layers. Under pressure, these layers can slide over each other—this is why pure gold or copper is so soft.

Alloying introduces “impurities” that disrupt these slip planes. There are two primary ways this happens:

1. Substitutional Alloys

The added atoms are of a similar size to the host atoms and simply take their place in the lattice. This disrupts the uniformity of the crystal, making it harder for layers to slide.

Examples: Brass (Copper and Zinc) and Bronze (Copper and Tin).

2. Interstitial Alloys

The added atoms (like Carbon or Nitrogen) are much smaller and lodge themselves in the “holes” or interstices between the larger host atoms. This acts as a microscopic “pin,” locking the larger atoms in place.

Example: Steel (Iron and Carbon).

IV. Key Characteristics and Properties

While every alloy is unique, they generally share several advantages over pure metals:

Enhanced Mechanical Strength: Lattice disruption makes the material more resistant to deformation.

Corrosion Resistance: Elements like Chromium in stainless steel react with oxygen to form a microscopic “passive layer” that prevents rust.

Customizability: We can tune thermal expansion, magnetism, and melting points.

Reduced Conductivity: It is important to note that alloys usually have lower electrical and thermal conductivity than pure metals because the foreign atoms interfere with the flow of electrons.

V. Common Types of Alloys and Their Applications

| Alloy Type | Primary Composition | Key Benefits | Common Applications |

| Steel | Iron + Carbon (<2%) | High tensile strength, cost-effective | Infrastructure, car bodies, tools |

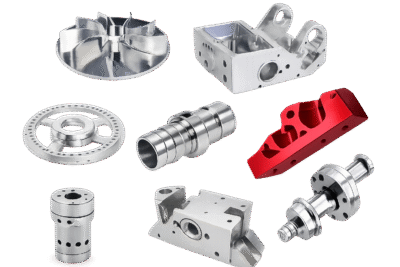

| Aluminum 6061 | Aluminum + Magnesium + Silicon | Lightweight, excellent corrosion resistance | Aircraft frames, bicycle frames, CNC parts |

| Titanium Alloys | Titanium + Aluminum + Vanadium | Incredible strength-to-weight, biocompatible | Medical implants (joints), jet engines |

| Brass | Copper + Zinc | Low friction, acoustic properties | Musical instruments, locks, ammunition |

| Nickel Alloys | Nickel + Chromium + Iron | Extreme heat resistance | Turbine blades, rocket components |

VI. Benefits and Limitations

The Benefits

Versatility: Thousands of alloys exist, each tailored for a specific niche.

Durability: Alloys survive longer in harsh environments (saltwater, high heat).

Hardness: They resist wear and abrasion much better than soft pure metals.

The Limitations

Reduced Ductility: As metals become harder through alloying, they often become more brittle and difficult to shape without cracking.

Recycling Challenges: Separating the constituent elements of an alloy is chemically complex and energy-intensive.

Welding Difficulty: The different melting points of the components can make certain alloys prone to “hot cracking” during welding.

Conclusion

Alloys are the unsung heroes of the technological age. By manipulating the atomic lattice through substitutional and interstitial placements, we have moved beyond the soft metals provided by nature to create materials that can withstand the vacuum of space and the pressures of the deep ocean.

FAQs

1. Why do alloys generally have lower electrical conductivity than pure metals?

In a pure metal, electrons flow relatively freely through a uniform crystal lattice. When you create an alloy, you introduce foreign atoms (solutes) that disrupt the regularity of that lattice. These “impurities” act as scattering centers for electrons, increasing electrical resistance. For example, while pure copper is an excellent conductor, adding zinc to create brass significantly reduces its efficiency in carrying electricity.

2. How does “Work Hardening” differ from “Alloying” in terms of strengthening a metal?

Alloying is a chemical method of strengthening; it changes the material’s composition by adding atoms to disrupt the lattice. Work hardening (or cold working) is a mechanical method. It involves deforming the metal (like hammering or rolling) to create “dislocations” within the crystal structure. These dislocations eventually tangle up, making it harder for the metal to deform further. Often, alloys are work-hardened to achieve even higher strength levels than alloying alone could provide.

3. Can an alloy be both substitutional and interstitial at the same time?

Yes, many complex industrial alloys are both. A prime example is Stainless Steel. It is primarily an interstitial alloy because carbon atoms fit into the gaps between iron atoms. However, it also functions as a substitutional alloy because large amounts of chromium and nickel atoms replace iron atoms directly in the lattice sites to provide corrosion resistance and stability.

4. Why is the “Strength-to-Weight Ratio” so much better in Aluminum alloys compared to Steel, even if Steel is stronger?

While steel has higher absolute strength, it is very dense (about 7.8g/cm³. Aluminum is much lighter (about 2.7g/cm³). By alloying aluminum with elements like Zinc or Magnesium (as seen in 7075 Aluminum), we can increase its strength significantly while maintaining its low density. This results in a material that can support a high load relative to its own mass, which is why it is preferred for aircraft fuselages over steel.

5. What is “Galvanic Corrosion,” and why is it a bigger concern for alloys?

Galvanic corrosion occurs when two dissimilar metals are in electrical contact in the presence of an electrolyte (like saltwater). Because alloys contain multiple elements, they can sometimes experience intergranular corrosion, where the boundaries between different microscopic crystals within the alloy act as different metals. One part of the alloy effectively “eats” the other, leading to structural failure even if the surface looks fine.

6. How does the cooling rate during the making of an alloy affect its final properties?

The cooling rate determines the grain size (the size of the individual crystals). Rapid cooling (quenching) typically results in smaller grains, which generally makes the alloy harder and stronger because there are more grain boundaries to block atomic slippage. Slow cooling allows for larger grains, which usually makes the material more ductile and easier to machine but less strong.

7. Are there non-metallic alloys?

By strict metallurgical definition, an alloy must have a metallic base. However, the term is sometimes used loosely in other fields. For example, in polymer science, a “polymer alloy” refers to a blend of two or more plastics to achieve better impact resistance or heat deflection, similar to how we blend metals.

8. Why are Titanium alloys considered “Biocompatible” for medical implants?

Titanium alloys (like Ti-6Al-4V) are biocompatible because they instantly form a highly stable, tenacious oxide layer when exposed to oxygen. This layer is chemically inert, meaning it does not react with human tissue or body fluids. Furthermore, the elastic modulus of certain titanium alloys is closer to that of human bone than stainless steel, reducing the risk of “stress shielding” where the implant takes too much load and causes the surrounding bone to weaken. Contact us for more information.